Mary Hilliard-Smith submitted a harrowing story to children’s magazine The Young Australia in 1896, regarding the loss of her little brother, Sid. The story tells of the subsequent search, and ultimate discovery of the boy deceased.

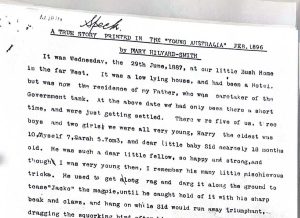

“A TRUE STORY PRINTED IN ‘THE YOUNG AUSTRALIA’ FEB 1896

By MARY HILYARD SMITH

It was Wednesday, the 29th June 1887, at our little Bush Home in the far West. It was a low lying house and had been a Hotel but was now the residence of my father, who was caretaker of the government tank. At the above date we had only been there a short time, and were just getting settled. There were five of us, three boys and two girls, we were all very young; Harry the eldest was 10, Myself 7, Sarah 5, Tom 3, and dear little baby Sid scarcely 18 months old. He was such a dear little fellow , so happy and strong, and though I was very young then, I remember his many little mischievous tricks. He used to get a long rag and drag it along the ground to tease ‘Jacko’ the magpie, until he caught hold of it with his sharp beak and claws, and hang on while Sid would run away triumphant, dragging the scorching bird after him, and the house would re-echo with his happy little laugh and brave attempt at talking.

On the Wednesday I speak of it was a washing day and we children were playing in the old kitchen at the back of the house. Sid was playing with two little dogs on the floor, Mother, Father and Tom (a man father employed to clean some drains) were at dinner inside. The Dining-room was ill furnished as yet, in one corner was a small sofa, in another a cupboard, and in the centre of the room a small table on which the dinner was laid. The room was lined and ceiled with cheap calico with a coloured picture pasted here and there on the walls. The earthen floor was covered with bags kept slightly damp for coolness. The room could not boast of chairs as yet, so small boxes were used instead, for in those days it was no easy matter to get to town, the nearest was sixty miles away and across rough and boggy country at that. On this day, as I say, our parents were at dinner, and we were waiting to be called. At last came the summons, and we all trooped into the room. Mother looked from one to another of us as we took our places, at last she said “where’s Sid?” We all looked at each other, and all rose and simultaneously ran into the kitchen. But he wasn’t there; Mother plunged her arms up to the elbows in the larges wash tub, then quickly drew them out again. We ran hither and thither, looked under the beds, into boxes, in fact every conceivable place. We came in and told Father.

“What child is missing?” asked Tom (the man I have spoken of)

“Sid, the baby” Mother answered, wringing her hands and beginning to cry.

“The one with the red jacket?” he asked quickly.

“Yes” we answered.

“Why, he followed the boss down to the big tank when he came to call me to dinner, he had no hat on, and I could see his little white head above the long grass.”

Now the way father had gone to call Tom was about three or four hundred yards in front of the house. Mother went at once to see if she could find him, while we little children were told to stay at home. It was about 2 O’clock when Sid was first missed, and it was about 5 O’clock before we could do anything but look near the place, for Harry had our only saddle horse away to a neighbouring station for mutton.

When he returned Father sent him over to Curraweena Station to seek assistance. As I had said we had only been at Helman’s Tank a short time, and had not become acquainted with any of the neighbours. Tom persisted in saying he had seen the child opposite the house, so the most valuable time was spent searching in that direction.

There was a slight shower that evening, not much, but enough to obliterate tall tracks. Mother and Father were besides themselves with grief, and to make matters worse, father was ill. At eleven that night a buggy and 25 mounted men came over from Curraweena Station and all through the long raining night they searched for the little wanderer.

Early next morning, Mr L…., the Manager of Curraweena Station came over with more men. He also brought grappling irons to drag the tanks with, he said he felt sure the child was in the tank, but all that Thursday he dragged in vain. All that night the men came and went, each hoping the other had brought back the little lost one. It was drizzling rain and the men’s horses were weary for they were shearers and were waiting for the roll call at Curraweena. About 40 men were searching near and far in every direction, but yet another day drew to a close and still poor little Sid was not found.

Mother was not allowed to go out, the men were good honest hearted fellows and spoke cheerfully and hopefully to her and told her to keep plenty of hot water to give the child a hot bath, and to keep some gruel ready. None but those who have gone through it know what great grief and anxiety was in our little home, we had begun to fear that our darling baby would never be restored to us alive.

All day Saturday and Sunday they were searching, at Mid-day Sunday the rain ceased and the sun shone. That night the men came in jaded and weary, they came to father and said;

“We are very sorry boss, but our horses are done, they are both foot sore and leg weary. Most of them have travelled from Queensland. Though the child must be dead by now, we would only be too glad to help if you could get horses, or if you can’t we will search on foot.”

But father thanked them, and the next morning they returned to Curraweena Station. The police and a tracker had been out, but had not been able to do anything, so had gone back again. Poor little Sid, five terrible days he had been in the bush, and still he was lost.

On Tuesday following the abandonment of the search, two men were riding their horses bare-backed to a tank two miles at the back of our place. They went to one side of the tank, but finding it very muddy they went to the other side. As they were riding around they noticed an old ale case close to the water’s edge. They were riding single file. The leader passed the box – his horse knocked against it. The second was about to pass on when suddenly his horse shied, the rider naturally turned to see what had caused the horse’s fright, and there in the old box lay all that remained earthly of poor baby Sid. No doubt when the weary little wanderer crawled into the box and went to sleep he thought he was home.

The brought him home. Poor little fellow, he looked just as if his tired little soul had fled while he slept. His little woollen socks and dress were thick with sharp grass seeds. Mother laid him across her knees and drew off his little boots, and to look at him you would think he was not ‘dead’ but sleeping. His limbs were quite limp and his flesh soft, I don’t think he had been dead long, though he had been seven days in the bush.

We buried him without sight of the house, and if any reader should travel this road and pass Helman’s if they look to the East, they will see the little white palings standing by the great Wilga tree, and they will not forget that it marks the resting place of my little brother Sid.”