The first of the eighteen to be called into existence was the bark-roofed Cobar Hotel, built before the town had been surveyed and laid out. It existed on what was then the corner road leading westward out of town, catching all the passing trade. Several prominent Cobar people held the licence, including Frederick Toy, for whom Frederick Street is named.

Other hotels followed, with some, such as the Turf, lasting only a year or two, while others remained in business for a century and sometimes more.

In 1894, Freeman’s Journal noted that:

“Eight hotels purvey for the fermented and spirituous requirements of the inhabitants, which, considering that labour is in the driest section of the ‘dry country’, are pretty extensive.”

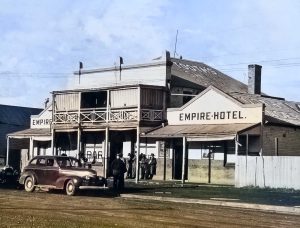

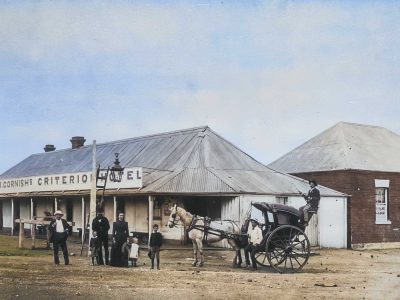

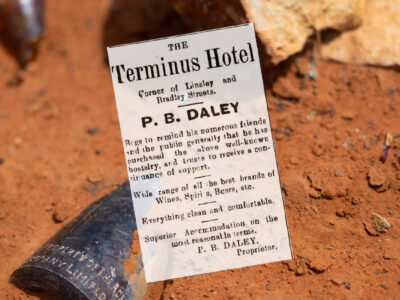

The eight hotels of 1894 were Crow’s Court House; the Victoria, under licence to Joseph Tunchon; Daniel Maher’s Star Hotel (a jewel of the west); the Royal Hotel; the Metropolitan under James Loughman; the Railway Hotel, associated with the interestingly hard-working and hard-living Susan Ross; Alderman and Mayor Hopkin Lewis’s Empire; and Poppa Cornish’s Criterion over in the sometimes somewhat louche East Cobar, where sly grog shanties and opium dens lurked beside the respectable miners’ homes.

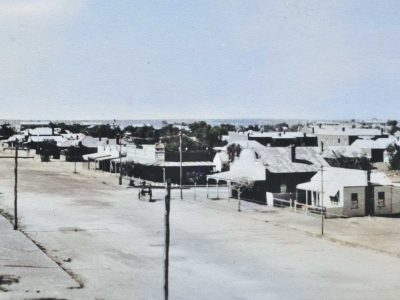

Four years later, in 1898, the glory days of the Great Western and Grand Hotels arrived. Both of these two-storey establishments were on the main street. The Great Western presided regally from its eastern corner while the Grand once dominated the western block. Their magnificent verandahs with cast iron lace hosted dinner parties with dignitaries, acted as platforms for politicians on the hustings, and viewing platforms for parades, processions and, in 1917, a riot between opposing forces of unionists and Wobblies.

Payday at the mines led to wild nights in the pubs, but the more sedate late-night shopping on Thursdays saw bands playing and families strolling the streets. Billiards was played in the saloons attached to the hotels, but respectable women knew better than to go anywhere near them. The miners could get bed and board at the hotels or go to the Oyster saloon for a change, while ladies dined at the Winter Garden Café, drinking sparkling water to avoid typhoid or the deceptively alcoholic schnapps to fix an upset digestion.

All of this ended with the catastrophic downturn in Cobar’s fortunes after World War 1. The mines closed and 90% of the population left town, leaving few customers for the hotels. Changes in licensing laws in the early 1920s encouraged many publicans to give up their licences, and so all went quiet for a while on this western front.

The fortunes of the town and the fate of the pubs continued to rise and fall, following not only mining and economic affairs but also changing social conditions. The Star was reincarnated as the New Occidental Hotel in 1939, and following another upswing of mining fortunes in the 1960s, the Grand gained a new, modern look, stripped of its verandahs. The Empire Hotel was demolished and rebuilt, and the era of licensed clubs arrived with the Returned Services and the Bowling and Golf Clubs rivalling the hotels in entertainment.

Of the eighteen hotels that have existed, only four of the buildings still stand in Cobar: The Empire, the Great Western, the Grand and the Court House. The other hotels met various fates, some destroyed by fire, several delicensed and turned into boarding houses before eventual decay, and many either dismantled or left derelict until finally removed.

The Eighteen Hotels of Cobar

-

Tattersall’s

-

Metropolitan

-

Commercial

-

Turf Club

-

Globe / Royal

-

Cobar

-

Victoria

-

Railway

-

Miners Arms

Brewing up a storm

Pubs sprang up all over Cobar, and so did breweries. Four breweries are known to have operated in the town. They were the Fair Hill, the Young Castlemaine, the Marshall Street, and the Standard.

The Fair Hill Brewery – an optimistic name if ever there was one – was established out of town on the Louth Road. It was registered by Thomas O’Brien in 1879, but he quickly sold it to John Parker. At that time, there would have been a lot of passing traffic travelling from Cobar to the river port of Louth, including ore from the mines. Once the railway line reached Nyngan in 1883, this decreased sharply, isolating the brewery and making it unprofitable.

Water for the brewery was supplied from a tank known as the Brewery Tank, which kept this name long after the brewery itself closed down around 1885. Eventually, the tank became part of Cobar’s new water supply scheme, by which time the ‘dead animals of the horse persuasion’ that littered its sides, had presumably been removed.

From The National Advocate, 24 October 1899:

“John Parker was also a butcher, a trade he continued after the brewery closed. He served for a time as an Alderman, elected in 1885 to replace Anthony Brough, who had resigned. Parker declared bankruptcy in 1887, but continued working as a butcher. In 1903, he was convicted of attempted rape, committed against a woman who was a customer on his meat cart round, and sentenced to three years in gaol. It appears he was still working as a butcher, but employed in someone’s business as a delivery driver.

The Young Castlemaine Brewery was the longest-lived of the Cobar breweries, lasting eleven years. It was in Cornishtown, an area to the east of the main township. Populated mostly by mine workers and their families, this was also something of a light industrial area.

Lewis and Freeman are two names that resound in Cobar history. Hopkin Lewis was among the first six aldermen of Cobar, elected in 1884 after the town was proclaimed. He became the first mayor; three of the other aldermen having previously declined the honour. He was also the builder, owner and licensee of the Empire Hotel. After his death in 1895, his widow Matilda became the proprietor.

Ned Freeman, Hopkin Lewis’ brewery business partner, was also a publican. The brewery side of the business closed down when Lewis died, but Freeman continued making cordial. His family later ran the Railway Hotel.

The Marshall Street Brewery, 1880-1886, was on the main street at the eastern end of town. There were hotels to either side within a very short distance, Maher’s Star Hotel and Mrs Hayes’ Commercial Hotel. There were many other hotels in the side streets, providing a good customer base.

The brewery was started by Samuel Williams and later owned by Hugh Sutherland. Mr Sutherland was a prominent local builder, responsible for the Town Hall, the Court House and the Public School as well as other important public buildings. It is possible he also built the brewery. For him, it was a sideshow to his main business, selling out to John Grady in the mid-1880s. After Grady’s death in 1892, the site was re-purposed by long-term resident Wong Wah Gee for his general store, Fong Wah Lee. The deep brewery cellars were useful for storing goods, but were a costly nuisance in rain storms when inadequate street drainage caused them to flood. In 1911, after one such event, the shop held a big sale of tinned goods that had the labels washed off – a bit of a lucky dip. Would it be fruit or fish, pickles or pigs’ trotters?

The last brewery opened in Cobar was Wood’s Standard Brewery (1888-1894). The location of the brewery is not known, but as Mr Wood was already operating a cordial factory, it is likely the brewery was added to those premises. Cordial factories often went with hotels or refreshment houses, which indicates a site somewhere in the main retail area of town.

Samuel Rupert Wood was the typical entrepreneurial early Cobar settler. As well as brewing and cordial manufacturing, he was an auctioneer and property manager for business and residential premises. He was a long-serving alderman, including a term as mayor. He was very active in his council role, everything to do with Cobar being inside his areas of interest. His letters to the newspaper to inform the public ,or to dispute or correct published reports, were frequent and not without humour. In a detailed letter of 1910, he advised the editor to “note the following and paste it in your hat”. When he had finished telling the reader which way was up and what was what, he ended the letter with “nuff said”. In 1916, he wrote a more sombre letter, thanking the people who had organised a farewell for his son, who had enlisted and was leaving for the Western Front. Mr Wood had been unable to speak, writing that “I did not feel equal to the occasion”.

What killed the breweries?

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, excise duties were introduced on beer. To be able to carry these taxes and remain profitable, a business needed to be of a reasonably large size, close to markets, and to have a minimum of other restraints.

Cobar, alas, had a market that was limited by a relatively small and fluctuating population (even though it was a population with a huge thirst). Transport was a problem partly because of the costs involved, especially before the coming of the railway, and partly because of the amount of time it took to get goods to market: beer had a shelf-life. Lack of a reliable supply of water, let alone water of sufficient quality, was another issue. Last and never least, the brewing of beer is best done in a climate where the temperature can be reasonably controlled in a range of about 50-65° F (10-20°C). That does not describe a typical summer day in Cobar, when the mildest description of the weather said it was ‘trying’. Of course, you could also expect to have flies, sand and dust as a regular addition to your beverage.