Along the way, the pise-walled Glenariff changing station offered weary passengers the luxury of a meal and a three-person toilet seat, before embarking on another 20 bone-jarring miles to the Byrock water holes and a welcome rest at The Mulga Creek Hotel.

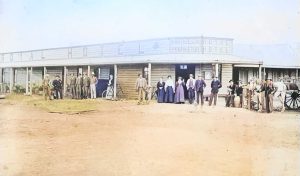

In 1877, a government decision to divert the river boat trade, taking the lucrative western wool clip away from the port of Bourke to Victoria and South Australia into Sydney, saw the twin ribbons of rail accelerate away from Orange. At the end of seven years of robust building, Byrock became a temporary terminus before the last push to the Darling. A city of navvies’ tents mushroomed, along with 10 stores, a butcher’s shop, a baker’s shop and no less than five hotels.

Author Ion Idriess left a colourful eyewitness description of life in temporary railway towns like Byrock. “On the verandah of the New Pub, the publican stood frowning down the road at the Old Pub. The New Pub had been built to help assuage the thirst of the navvies… now the hard-toiling, hard-drinking Knights of the Pick and Shovel were slaving a few miles farther on, their white tents and hessian huts stretching a mile.

Thus, the turbulent gangs had toiled on…Vanished the sun-glint on the long line of shovel blades, the up and down of the picks, the shouts of the sleeper haulers, the creaking wheels of the drays and wagons, clanging of hammers, mingled sweat of straining teams and gangs of men, the fire and song from the black-smiths’ and tool-sharpeners’ anvils… Those navvies lived hard. Played hard, too.”

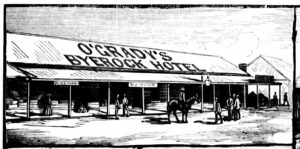

Linking Sydney to the bush heralded Byrock’s moment of glory, and for 12 months or so the hotels did a roaring trade. A visitor reported that O’Grady’s Byerock Hotel was “an airy and commodious structure, gives good bed and board, dispenses a fine brew, and seems to eschew those cheap abominations in ‘fermented and spirituous liquor’ which have been only to truly described as ‘liquid fire and distilled damnation.’”

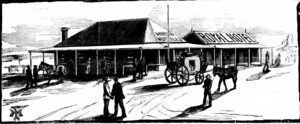

At the upmarket, 14-room Royal, the courteous host catered for gentlemen and offered fine cuisine. The Carriers Arms was neat and comfortable and The Commercial was greatly fancied by the ‘bone and sinew’ of the bush.

Along with the 650 railway workers came crowds of thirsty and hungry shearers, drovers and teamsters, as well as train travellers. One visitor complained of the “dust fiend” that made life unbearable as hotels closed windows and doors tight in the stifling summer heat.

With the arrival of the train, Cobb & Co started offering a service to Bourke four times weekly. The fifty-mile trip took 12 hours and there were complaints about the swearing when navvies climbed aboard. By 1884, five hundred people were living in the area and the optimistic New South Wales government was soon offering prime blocks of land for sale. But as the railway work faded, so did the town and most of the blocks are still unsold.

As the population dwindled, shops and pubs went up for sale. The fact that household water had to be brought in by rail from Narromine crippled potential and buyers were scarce. In 1902, a possible ‘insurance fire’ reduced the Royal Hotel to ashes along with the neighbouring tobacconist and hair saloon. The old Byerock Hotel had a miraculous delivery. Salvation came in the form of the purchasing Presbyterian minister who, in 1919, utilised the timber and iron to erect churches in Louth, Byrock and Brewarrina. Just as well those walls couldn’t speak!

At the time the railway finally swept across the Darling flood plain to reach Bourke, it was the longest stretch of straight railway line in the world – 116 miles (187 km). His Excellency the Governor opened the Great Western Line in September 1885 amid rhetoric that “the eastern seaboard was now married to the mighty River Darling, not with a golden hoop, but with a strong iron band.” Humble Byrock had played its part in the wedding and then stepped off-stage.

The present Mulga Creek Hotel caters well for locals and a steady stream of tourists. These walls do tell a story – of local heroes like Lachlan McLachlan who earned the Military Medal for Bravery in the bitter battle of Ypres in 1917. Takings from parking meters outside support the Flying Doctor Service, which can taxi right up to pub should any patron need attention!

Today

Mulga Creek Hotel

The Mulga Creek Hotel is a classic bush pub with old stylings in a modern, solid brick building.

Byrock

One of the smaller villages of the Bourke Shire, Byrock has an interesting and colourful past intersecting with coach, rail and road.